The organisation of forced labour in Italy (1943-1945)

The Paladino Propaganda

Working for the Paladino was not without risks.

Getting to work by bicycle or by lorry exposed the workers to being machined-gunned from the air; the building sites were targets for the bombers; clearing up the rubble in the cities following an air raid exposed the workers to the dangers of unexploded bombs or the collapse of damaged buildings.

But being in possession of a document released by the Military Inspectorate at least ensured them against being press-ganged by the Germans or rounded up by the Fascists. And this was what General Paladino's propaganda sought to exploit.

One of his posters, probably published at the start of 1944, made things very clear on that score:

“Workers!

The present situation does not allow everyone to carry out his preferred trade, but requires that all take on whatever work is urgently needed for the defence of the Nation.

This Military Labour Inspectorate, whose motto is Bread and Work, is dedicated to this reconstruction […]

All of you will be properly recompensed: food will be free, abundant and guaranteed; protection will be assured in respect of both the German and Italian authorities; other than this, the document which attests your belonging to the Military Labour Inspectorate will be released immediately upon enrolment and will guarantee that your work will be confined to Italy, as far as possible in your own region, and will exonerate you from being called up for military service or other obligatory call-ups. This will be exactly in line with what has been agreed with the interested authorities.

Irrespective of your personal situation or age with regard to military service, report with confidence to the recruiting office. […].”1

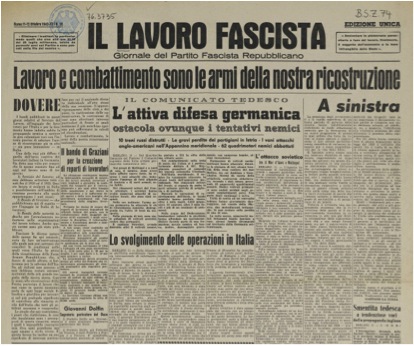

This indicates a fairly evident change of approach from that used in the earlier Paladino campaigns or in the official propaganda campaigns of the RSI. The earliest appeals, in fact, had played upon the sense of duty and the need to rebuild the homeland that had been destroyed by invasions and air raids. The 29-30 September 1943 edition of “Fascist Labour”carried a full-page headline with the words: “Rebuilding the Fatherland by means of Labour and Arms”. Afterwards there followed an article explaining the purpose of the General Inspectorate and its workers. There was no reference to fascism but only only to one's duty to one's country.

Also, in the only edition of “The Workers' Way”, which came out in October and was published by the Inspectorate, there was an article by Paladino himself who asked the workers to do their duty in respect of the Fatherland without making any reference to fascism, which he took good care not to nominate.“Suddenly that national order of things – wrote Paladino – that, despite the scars of war, assured an honourable occupation and bread on the table for everyone, is no more.2

Evidently these appeals to patriotism did not produce the desired effect, and Paladino, as has been demonstrated, put more emphasis on assuring the men that the Inspectorate protected them from being sent to work in Germany and from being called up for military service.

Other than the specifically stated propaganda, Paladino sought to promote the maximum cohesion amongst his “troops”, pushing the officers into establishing close relationships with the labour force, personally inspecting a large number of battalions, and rewarding the most deserving workers. He attempted to bring about some form of 'esprit de corps' by organising paramilitary ceremonies such as the “handing over of the flame” which recalled the handing over of the flag to the troops, prize-giving ceremonies, and the raising of morale, the latter through the setting up of a body of military chaplains.

In short, it was intended that the Paladino should not resemble a body of shirkers but become a homogeneous organisation in which the workers could regain their self-esteem.

Moreover, after the spring of 1944, some labourers' battalions were created from youngsters who had been avoiding the call-up and from partisans who had taken advantage of Mussolini's amnesty, granted in the May of that same year. Several thousand partisans and draft-dodgers took advantage of this opportunity even though they had little faith in the enterprise both from a political and practical point of view.

by Amedeo Osti Guerrazzi (2016)

Diario Storico della Organizzazione Paladino.

A Raccolta!, “La via dei lavoratori”, numero unico, ottobre 1943.

The workers' re-education camps (AEL) were set up in 1940 by the Gestapo in order to re-educate individuals accused of acts of industrial sabotage or who, for some reason, were held to be “reluctant” to work. In effect, these camps were also a means of exploiting forced labour. It has been estimated that in Germany and the German-occupied territories around 200 Arbeitserziehungslager had been set up in which around 500,000 people had been imprisoned.

During the Second World War the Germans established prisoner of war units known as Bau-und Arbeits Battaillon (shortened to B.A.B.). The B.A.B. were made up on average of 600 prisoners of war who were used as forced labour. The distinguishing feature of these forced labour units was that they were mobile; unlike the prisoners who were being held in the Stalag, these workers were not stationed in a specific location but were moved around according to necessity.

The I.G. Farben Company was founded in 1925 from the merger of several different German industries. During the Second World War it was the main producer of chemicals for Nazi Germany. I.G. Farben made more use of forced labour than any other industry, particularly during the construction of the plants at Auschwitz. The directors of I.G. Farben were among the accused at the Nuremberg Trials of 1947/48. At the end of the war the decision was taken to split up the industry into its original component parts.

The Arbeitskommando were work camps detachments for prisoners who had been captured by the Germans. Usually made up of a few hundred prisoners, they were set up near to places of employment (factories, mines, agricultural establishments etc.). They were run from a central Stalag (prisoner of war camp), which may have been responsible for hundreds of work detachments. The work detachments for Allied prisoners of war were visited on a regular basis by representatives of the Red Cross.

The Military Work Inspectorate was set up in October 1943 with the aim of organising a workforce which was to construct territorial defences for the Italian Republic of Salò and repair the damage caused by air raids. Known as the “Organizzazione Paladino” (Paladino Organisation) after its founder and commanding officer, and operating in strict collaboration with, and at times directly employed by, the Germans, it took on several tens of thousands of workers.

The Todt Organisation was begun in Germany at the end of the 'Thirties with the aim of setting up a workforce which would build military defences. The idea of Fritz Todd, who was also its director until his death in 1942, during the war it exploited forced labour in German-occupied countries. In Italy it played a fundamental role in the construction of defences along the Appenines in support of the Wehrmacht, employing tens of thousands of men.

Born in Scilla (Reggio Calabria) in 1890, he volunteered for the Corps of Engineers as a telegraphist in 1907. In 1908 he rose to the rank of sergeant, a rank he held throughout the War in Libya. In 1914 he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and during the First World War he was made captain.

Afterwards he remained in the Armed Forces and in 1932 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1936 he took part in the War in Ethiopia, during which he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the Second World War, he returned to Italy after participating in the Greek campaign and was assigned to the Bolzano Corps. In 1942 he was promoted to brigader general. After the armistice he joined the Italian Social Republic for which he created the Military Labour Inspectorate.

He finally retired in 1945 and in 1970 he was awarded the honorary grade of major general.

He died in 1974.

Fritz Sauckel, born in 1894, was a local Nazi party official. In 1942 he was nominated plenipotentiary for the organisation of work throughout all the German-occupied territories. In practice, he was responsible for the compulsory engagement of forced labour. In Italy his organisation tried to round up hundreds of thousands of men to send to the German Reich, with scarce results. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to death, the sentence being carried out in 1946.

Albert Speer, born in 1905, was an architect who enjoyed an excellent personal relationship with Adolf Hitler. Even though he was not an ardent Nazi, he was the brains behind the staging of the Party parades, thereby assuring for himself the esteem and trust of the dictator. In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt, he was put in charge of the Ministry of Arms and Munitions, which oversaw the Todt organisation. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to twenty years imprisonment. He died in London in 1981.

A German prisoner of war camp. The living conditions in the Stalag varied considerably according to the nationality of the prisoners (Allied, Russian, Italian military internees, etc.)

Fritz Todt was a German engineer who was responsible, in the 'Thirties, for building the motorway system as desired by Hitler. At the end of the 'Thirties he set up the Todt Organisation, with the aim of supplying forced labour to be used in the building of defences along the French border. During the war his organisation oversaw the use of forced labour in the occupied territories. He died in a plane crash in 1942.

The Gemeinschaftslager, like the Wohnlager, were unsupervised camps for foreign workers, while the Arbeitslager were supervised. Generally speaking, the concept of forced labour is applied only to the latter, but at the present time historians are undoubtedly tending to review the concept of forced labour, extending it to include work situations which are apparently free but in reality are forced. More specifically, the current discussion tends to be orientated towards a concept of forced labour which includes these three distinctive elements:

- from a legal point of view, it is impossible for the worker to dissolve the relationship with his employer

- from the social point of view, the possibilities of significantly influencing employment conditions are limited

- there is a high mortality rate, which indicates a higher than average workload and a provision of means of sustenance below the necessary requirements.

See: [https://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/geschichte/auslaendisch/begriffe/index.html]

The workers' re-education camps (AEL) were set up in 1940 by the Gestapo in order to re-educate individuals accused of acts of industrial sabotage or who, for some reason, were held to be “reluctant” to work. In effect, these camps were also a means of exploiting forced labour. It has been estimated that in Germany and the German-occupied territories around 200 Arbeitserziehungslager had been set up in which around 500,000 people had been imprisoned.

During the Second World War the Germans established prisoner of war units known as Bau-und Arbeits Battaillon (shortened to B.A.B.). The B.A.B. were made up on average of 600 prisoners of war who were used as forced labour. The distinguishing feature of these forced labour units was that they were mobile; unlike the prisoners who were being held in the Stalag, these workers were not stationed in a specific location but were moved around according to necessity.

The I.G. Farben Company was founded in 1925 from the merger of several different German industries. During the Second World War it was the main producer of chemicals for Nazi Germany. I.G. Farben made more use of forced labour than any other industry, particularly during the construction of the plants at Auschwitz. The directors of I.G. Farben were among the accused at the Nuremberg Trials of 1947/48. At the end of the war the decision was taken to split up the industry into its original component parts.

The Arbeitskommando were work camps detachments for prisoners who had been captured by the Germans. Usually made up of a few hundred prisoners, they were set up near to places of employment (factories, mines, agricultural establishments etc.). They were run from a central Stalag (prisoner of war camp), which may have been responsible for hundreds of work detachments. The work detachments for Allied prisoners of war were visited on a regular basis by representatives of the Red Cross.

The Military Work Inspectorate was set up in October 1943 with the aim of organising a workforce which was to construct territorial defences for the Italian Republic of Salò and repair the damage caused by air raids. Known as the “Organizzazione Paladino” (Paladino Organisation) after its founder and commanding officer, and operating in strict collaboration with, and at times directly employed by, the Germans, it took on several tens of thousands of workers.

The Todt Organisation was begun in Germany at the end of the 'Thirties with the aim of setting up a workforce which would build military defences. The idea of Fritz Todd, who was also its director until his death in 1942, during the war it exploited forced labour in German-occupied countries. In Italy it played a fundamental role in the construction of defences along the Appenines in support of the Wehrmacht, employing tens of thousands of men.

Born in Scilla (Reggio Calabria) in 1890, he volunteered for the Corps of Engineers as a telegraphist in 1907. In 1908 he rose to the rank of sergeant, a rank he held throughout the War in Libya. In 1914 he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and during the First World War he was made captain.

Afterwards he remained in the Armed Forces and in 1932 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1936 he took part in the War in Ethiopia, during which he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the Second World War, he returned to Italy after participating in the Greek campaign and was assigned to the Bolzano Corps. In 1942 he was promoted to brigader general. After the armistice he joined the Italian Social Republic for which he created the Military Labour Inspectorate.

He finally retired in 1945 and in 1970 he was awarded the honorary grade of major general.

He died in 1974.

Fritz Sauckel, born in 1894, was a local Nazi party official. In 1942 he was nominated plenipotentiary for the organisation of work throughout all the German-occupied territories. In practice, he was responsible for the compulsory engagement of forced labour. In Italy his organisation tried to round up hundreds of thousands of men to send to the German Reich, with scarce results. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to death, the sentence being carried out in 1946.

Albert Speer, born in 1905, was an architect who enjoyed an excellent personal relationship with Adolf Hitler. Even though he was not an ardent Nazi, he was the brains behind the staging of the Party parades, thereby assuring for himself the esteem and trust of the dictator. In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt, he was put in charge of the Ministry of Arms and Munitions, which oversaw the Todt organisation. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to twenty years imprisonment. He died in London in 1981.

A German prisoner of war camp. The living conditions in the Stalag varied considerably according to the nationality of the prisoners (Allied, Russian, Italian military internees, etc.)

Fritz Todt was a German engineer who was responsible, in the 'Thirties, for building the motorway system as desired by Hitler. At the end of the 'Thirties he set up the Todt Organisation, with the aim of supplying forced labour to be used in the building of defences along the French border. During the war his organisation oversaw the use of forced labour in the occupied territories. He died in a plane crash in 1942.

The Gemeinschaftslager, like the Wohnlager, were unsupervised camps for foreign workers, while the Arbeitslager were supervised. Generally speaking, the concept of forced labour is applied only to the latter, but at the present time historians are undoubtedly tending to review the concept of forced labour, extending it to include work situations which are apparently free but in reality are forced. More specifically, the current discussion tends to be orientated towards a concept of forced labour which includes these three distinctive elements:

- from a legal point of view, it is impossible for the worker to dissolve the relationship with his employer

- from the social point of view, the possibilities of significantly influencing employment conditions are limited

- there is a high mortality rate, which indicates a higher than average workload and a provision of means of sustenance below the necessary requirements.

See: [https://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/geschichte/auslaendisch/begriffe/index.html]

The workers' re-education camps (AEL) were set up in 1940 by the Gestapo in order to re-educate individuals accused of acts of industrial sabotage or who, for some reason, were held to be “reluctant” to work. In effect, these camps were also a means of exploiting forced labour. It has been estimated that in Germany and the German-occupied territories around 200 Arbeitserziehungslager had been set up in which around 500,000 people had been imprisoned.

During the Second World War the Germans established prisoner of war units known as Bau-und Arbeits Battaillon (shortened to B.A.B.). The B.A.B. were made up on average of 600 prisoners of war who were used as forced labour. The distinguishing feature of these forced labour units was that they were mobile; unlike the prisoners who were being held in the Stalag, these workers were not stationed in a specific location but were moved around according to necessity.

The I.G. Farben Company was founded in 1925 from the merger of several different German industries. During the Second World War it was the main producer of chemicals for Nazi Germany. I.G. Farben made more use of forced labour than any other industry, particularly during the construction of the plants at Auschwitz. The directors of I.G. Farben were among the accused at the Nuremberg Trials of 1947/48. At the end of the war the decision was taken to split up the industry into its original component parts.

The Arbeitskommando were work camps detachments for prisoners who had been captured by the Germans. Usually made up of a few hundred prisoners, they were set up near to places of employment (factories, mines, agricultural establishments etc.). They were run from a central Stalag (prisoner of war camp), which may have been responsible for hundreds of work detachments. The work detachments for Allied prisoners of war were visited on a regular basis by representatives of the Red Cross.

The Military Work Inspectorate was set up in October 1943 with the aim of organising a workforce which was to construct territorial defences for the Italian Republic of Salò and repair the damage caused by air raids. Known as the “Organizzazione Paladino” (Paladino Organisation) after its founder and commanding officer, and operating in strict collaboration with, and at times directly employed by, the Germans, it took on several tens of thousands of workers.

The Todt Organisation was begun in Germany at the end of the 'Thirties with the aim of setting up a workforce which would build military defences. The idea of Fritz Todd, who was also its director until his death in 1942, during the war it exploited forced labour in German-occupied countries. In Italy it played a fundamental role in the construction of defences along the Appenines in support of the Wehrmacht, employing tens of thousands of men.

Born in Scilla (Reggio Calabria) in 1890, he volunteered for the Corps of Engineers as a telegraphist in 1907. In 1908 he rose to the rank of sergeant, a rank he held throughout the War in Libya. In 1914 he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and during the First World War he was made captain.

Afterwards he remained in the Armed Forces and in 1932 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1936 he took part in the War in Ethiopia, during which he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the Second World War, he returned to Italy after participating in the Greek campaign and was assigned to the Bolzano Corps. In 1942 he was promoted to brigader general. After the armistice he joined the Italian Social Republic for which he created the Military Labour Inspectorate.

He finally retired in 1945 and in 1970 he was awarded the honorary grade of major general.

He died in 1974.

Fritz Sauckel, born in 1894, was a local Nazi party official. In 1942 he was nominated plenipotentiary for the organisation of work throughout all the German-occupied territories. In practice, he was responsible for the compulsory engagement of forced labour. In Italy his organisation tried to round up hundreds of thousands of men to send to the German Reich, with scarce results. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to death, the sentence being carried out in 1946.

Albert Speer, born in 1905, was an architect who enjoyed an excellent personal relationship with Adolf Hitler. Even though he was not an ardent Nazi, he was the brains behind the staging of the Party parades, thereby assuring for himself the esteem and trust of the dictator. In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt, he was put in charge of the Ministry of Arms and Munitions, which oversaw the Todt organisation. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to twenty years imprisonment. He died in London in 1981.

Fritz Todt was a German engineer who was responsible, in the 'Thirties, for building the motorway system as desired by Hitler. At the end of the 'Thirties he set up the Todt Organisation, with the aim of supplying forced labour to be used in the building of defences along the French border. During the war his organisation oversaw the use of forced labour in the occupied territories. He died in a plane crash in 1942.

The workers' re-education camps (AEL) were set up in 1940 by the Gestapo in order to re-educate individuals accused of acts of industrial sabotage or who, for some reason, were held to be “reluctant” to work. In effect, these camps were also a means of exploiting forced labour. It has been estimated that in Germany and the German-occupied territories around 200 Arbeitserziehungslager had been set up in which around 500,000 people had been imprisoned.

During the Second World War the Germans established prisoner of war units known as Bau-und Arbeits Battaillon (shortened to B.A.B.). The B.A.B. were made up on average of 600 prisoners of war who were used as forced labour. The distinguishing feature of these forced labour units was that they were mobile; unlike the prisoners who were being held in the Stalag, these workers were not stationed in a specific location but were moved around according to necessity.

The I.G. Farben Company was founded in 1925 from the merger of several different German industries. During the Second World War it was the main producer of chemicals for Nazi Germany. I.G. Farben made more use of forced labour than any other industry, particularly during the construction of the plants at Auschwitz. The directors of I.G. Farben were among the accused at the Nuremberg Trials of 1947/48. At the end of the war the decision was taken to split up the industry into its original component parts.

The Arbeitskommando were work camps detachments for prisoners who had been captured by the Germans. Usually made up of a few hundred prisoners, they were set up near to places of employment (factories, mines, agricultural establishments etc.). They were run from a central Stalag (prisoner of war camp), which may have been responsible for hundreds of work detachments. The work detachments for Allied prisoners of war were visited on a regular basis by representatives of the Red Cross.

The Military Work Inspectorate was set up in October 1943 with the aim of organising a workforce which was to construct territorial defences for the Italian Republic of Salò and repair the damage caused by air raids. Known as the “Organizzazione Paladino” (Paladino Organisation) after its founder and commanding officer, and operating in strict collaboration with, and at times directly employed by, the Germans, it took on several tens of thousands of workers.

The Todt Organisation was begun in Germany at the end of the 'Thirties with the aim of setting up a workforce which would build military defences. The idea of Fritz Todd, who was also its director until his death in 1942, during the war it exploited forced labour in German-occupied countries. In Italy it played a fundamental role in the construction of defences along the Appenines in support of the Wehrmacht, employing tens of thousands of men.

Born in Scilla (Reggio Calabria) in 1890, he volunteered for the Corps of Engineers as a telegraphist in 1907. In 1908 he rose to the rank of sergeant, a rank he held throughout the War in Libya. In 1914 he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and during the First World War he was made captain.

Afterwards he remained in the Armed Forces and in 1932 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1936 he took part in the War in Ethiopia, during which he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the Second World War, he returned to Italy after participating in the Greek campaign and was assigned to the Bolzano Corps. In 1942 he was promoted to brigader general. After the armistice he joined the Italian Social Republic for which he created the Military Labour Inspectorate.

He finally retired in 1945 and in 1970 he was awarded the honorary grade of major general.

He died in 1974.

Fritz Sauckel, born in 1894, was a local Nazi party official. In 1942 he was nominated plenipotentiary for the organisation of work throughout all the German-occupied territories. In practice, he was responsible for the compulsory engagement of forced labour. In Italy his organisation tried to round up hundreds of thousands of men to send to the German Reich, with scarce results. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to death, the sentence being carried out in 1946.

Albert Speer, born in 1905, was an architect who enjoyed an excellent personal relationship with Adolf Hitler. Even though he was not an ardent Nazi, he was the brains behind the staging of the Party parades, thereby assuring for himself the esteem and trust of the dictator. In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt, he was put in charge of the Ministry of Arms and Munitions, which oversaw the Todt organisation. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to twenty years imprisonment. He died in London in 1981.

Fritz Todt was a German engineer who was responsible, in the 'Thirties, for building the motorway system as desired by Hitler. At the end of the 'Thirties he set up the Todt Organisation, with the aim of supplying forced labour to be used in the building of defences along the French border. During the war his organisation oversaw the use of forced labour in the occupied territories. He died in a plane crash in 1942.