Avgust Pirjevec (1887-1943)

A Slovene intellectual killed by Fascist and Nazi concentration camps

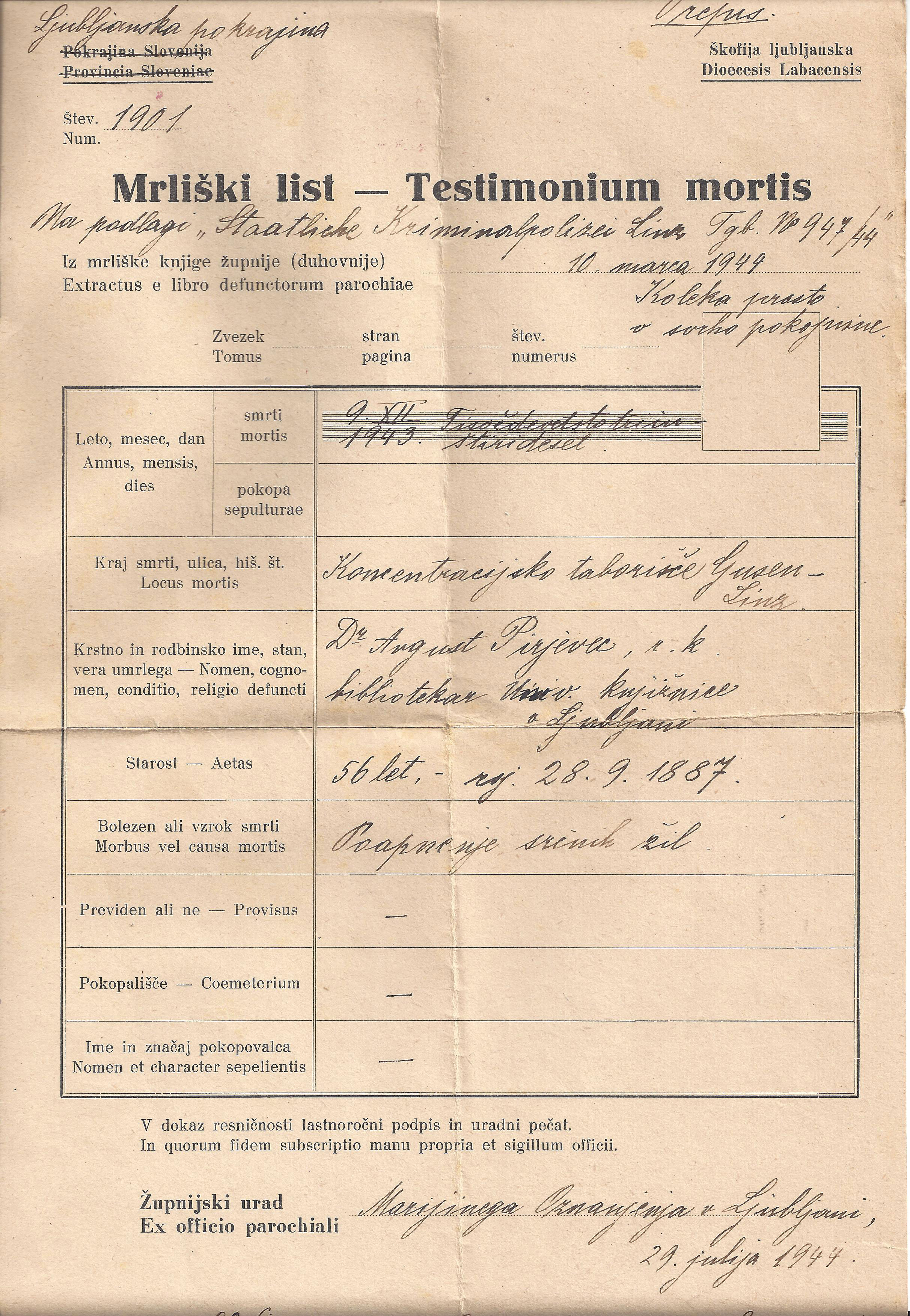

Slovene librarian, lexicographer, political and literary historian, Avgust Pirjevec was a respected multicultural and multilingual intellectual when his career and activities were violently terminated in 1943. On Sunday 9 May, during his visit to Dr. Munc's home in Ljubljana, members of the Italian occupying forces arrested him. As an activist of Liberation Front (OF), the main anti-fascist Slovene civil resistance and political organization, he was first taken to the Coroneo Prison in Trieste.

Later he was transferred to the Fascist concentration Camp for civilians at Cairo Montenotte in Italy and from there to the Nazi Concentration Camp at Mauthausen.

He died in Gusen Concentration Camp in December 1943.

Background

At the time of his arrest Avgust Pirjevec was a 56-year old husband, father of two grown-up children and the internationally respected and accomplished chief librarian of the National Research Library (today National and University Library of Slovenia). He was born into a Slovene family in Gorizia, at the time a multiethnic town under the Habsburg monarchy, in which Italian and Venetian, Slovene, Friulian and German were spoken.

He graduated from the University of Vienna in 1913, where he studied Slavic philology. During World War I he served in the Austro-Hungarian Army. After demobilization in 1917 he taught Slovene and German language in Trieste.

When the Austrian Littoral became part of the Kingdom of Italy fascism impacted on his life dramatically. He lost his job and moved to Ljubljana, in what was then the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. He started out as a professor and soon took up a position in a national library. He was renowned as a progressive and national liberal intellectual.

During World War II, his son Dušan Pirjevec (1921-1977) became an important resistance leader of the Yugoslav partisans in Slovenia; his daughter Ivica Pirjevec was active in the Liberation Front of the Slovenian People and was killed by the Nazis in 1944. His granddaughter Alenka Pirjevec (1945) has inherited the records of his arrests and internments from her grandmother Zora Pirjevec.

We learn about Avgust Pirjevec's arrests and internments from a handwritten note, saved in a cardboard box. On the top of a pile of 23 handwritten postcards and letters written in Italian, Slovene and even German we found a note Zora had written regarding her husband's multiple arrests and internments from 1941-1943. His arrests began in Šentvid, a village to the NW of Ljubljana, (today part of Ljubljana)under the German occupation and continued under Italian rule in the occupied province of Ljubljana.

Arrest Correspondence

From the Coroneo Prison (Carcere giudiziario)in Trieste he wrote short practical letters in Italian. The first three letters, addressed to his sister and brother, which date from 14 May onwards, express a concern for his wife and daughter.

The rest of the correspondence is practical: he needs money to spend on the food and drink he is allowed to buy. On the list of goods are: coffee, cheese and wine. He was asking them to send him underwear (basic or second-hand), soap, sandals,shorts, towels and socks. Eleven days after his arrest, he reports receiving money (300 Lire) and a parcel. One of the senders was Danilo from Trieste. He was still in need of underwear.

Finally he receives a parcel from Ljubljana and addresses a letter to his wife. He regularly receives food and money. Prison food is scarce, comprised of daily soup with rice or “maccaroni” (pasta)and 40 kg of bread. In prison he is allowed to buy cheese or salami once a week, potatoes twice, "caffelate" every other day, wine daily. Repeatedly he asks about Ivica, his daughter. As we learn she was arrested too. He is urging his family to send her food parcels.

Other important information from this prison correspondence reveals that he was arrested by “organi dell’ Ispettorato generale di pubblica sicurezza a Trieste” (letter n.5, 04.06.1943). He was subjected to interrogations, which however didn’t produce any results.

“I am healthy and I am doing fine,” are the usual concluding words Avgust writes to his wife.

His concern for the financial matters of his wife and the wellbeing of his daughter Ivica is constant. He is trying to be helpful from inside prison suggesting they should sublet a room in an apartment in Ljubljana and collect money from his academic papers from the period before the internment. He found the difficulty of communication with his wife very heavy to bear.

Cairo Montenotte Concentration Camp for Civilians

The correspondence from the Cairo Montenotte Concentration Camp for Civilians is more extensive. The first postcard is written in German and dated 14 July. He writes: “I left Trieste on 11th and arrived here on 12th. I am very happy to be able to breathe fresh air, the nights are cool and days windy.” Further he is asking her to send him the following: an old clothes brush, a briefcase, postcards, a notebook, needle and thread,… One postcard contains a request that she should contact a university rector and his faculty dean and obtain their confirmation that he was not politically active in the academic world. He writes that their testimonies could help to gain his release.

A greater number of postcards and letters from Cairo Montenotte have been preserved. The last two were sent from the transport taking him to the Nazi Concentration Camp. Summarizing, we learn he was receiving money from his family. His money was exchanged for vouchers to be spent in the concentration camp shop. He used to buy tomatoes, onions and fruit. He had requested ordinary objects to improve the circumstances of his internment, like clothing and writing supplies. Most of all he was missing tobacco, cigarette paper and matches. It is clearly stated that he was interned with “Primorci” - all Slovene nationals from the former Austrian Littoral and that they received goods by mail without restrictions.

Meals served to internees consisted of: black coffee in the morning, 1 1/4 of a bread roll(less than in prison), a ladle of soup at noon and another one in the evening. A concentration camp doctor diagnosed him as suffering from a mild form of TB (Tuberculosis). He was prescribed a quarter of a litre of milk. Later he paid shots of calcium.

Once he wrote about being wronged. The concentration camp administration intentionally destroyed his wife's postcards, received in prison. This must have affected him greatly since he is repeatedly encouraging his wife to write to him more often.

As an internee he had a permit to order and buy things from the town of Cairo Montenotte. He ordered a suitcase

He and other internees were not working. He missed being able to read. Time was passing by slowly, except when the internees had organised a chess tournament.

We read in letter n.16, dated 18.08., that Cairo Montenotte Concentration Camp was one of state’s best camps.

Two days after the armistice, regardless of the pressure exerted on their part, the internees are not given instructions to leave the concentration camp. At the end of postcard n. 19 he recommends his wife that she stops sending money. The situation was uncertain. The German army took over the concentration camp.

Cairo Montenotte under the Germans

From early September until the departure of a train on 8 October Avgust Pirjevec along with other internees was living with uncertainty. His correspondence is full of conjecture. As the status quo persisted he continued to send out requests to different people for tobacco, cigarette paper and matches.

In letter n.23, dated 25 September, he asks if his wife is wondering why he has not yet returned home. The armistice having been announced, the internees expected an immediate disbandment of the camp. According to his correspondence, Commander Passavanti [Pasquale Alessandro] was waiting for higher orders. He waited until the arrival of the German army. “Many German officers arrived at the camp but no decision was taken,” he wrote. Two higher Gestapo officials arrived at the camp. “We are at the start of something new. Probably they will interrogate us as to why we are here, or will they inspect our files from Trieste, or will they hand us over to the new Mussolini government or rather to the new republican fascist organisation?” As we can see, disorientation and uncertainty amongst the inmates was great.

In general, the internees were still expecting the camp to be disbande. August Pirjevec on the other hand was pessimistic and announced a further long stay in the camp. He was guessing again: “The elderly, children and sick inmates will go home, the young healthy men will be sent to work.” He wrote extensively about money matters in the camp. It was clear that they would leave without the money they had received which was deposited in the camp’s offices.

In a letter to Ida, dated 4 October, we read that there was a moment when the internees attempted an escape. Again he is blaming the concentration camp commander for not having allowed the internees to escape.

Under the Germans he wrote: “Everyone had to nominate a place he would go to in case he was released. I nominated Ljubljana and Rovato.” He is wondering about the transport home. How will they arrange travel for 1300 inmates? Will he be able to stop and visit Ida in Rovato? Will he receive a personal travel document?

On the other hand we find out that the Germans allowed the internees to visit the town of Cairo Montenotte. He went out once. A postcard addressed to his daughter confirms it. He met a shopkeeper who came from the Slovene speaking town of Tolmin, located in Primorska, the Littoral region in which his birth town was located. Immediately he arranged for money and goods to be sent to her address in Cairo Montenotte.

Last postcards before Mauthausen

Four postcards which have been kept, the last ones Avgust Pirjevec sent from the Cairo Montenotte concentration camp, are puzzling and provocative. He was not allowed to leave the concentration camp with the elderly and sick despite the fact that he had a record of illness. He announces the departure for an unknown destination listing: Como, Innsbruck and Linz. He is positive and predicts his release.

On Friday, 8 October, a train left the camp. Avgust was on the train. He wrote the last two postcards in pencil, one in Mantova, the other in Padova.

The postcard sent from Mantova says:

“Greetings from the journey to Innsbruck or Linz! I have received bread and other items. Love, A.”

The last postcard was supposedly sent from Padova as it says :

“Greetings from the journey from Padova to Mauthausen near Linz on Donau. Avgust”

A Former Internee's testimony

Avgust Pirjevec perished in Mauthausen Concentration camp 68 days after his arrival. At the time of his death at least two groups of Slovene and Croatian inmates, interned along with Pirjevec from Cairo Montenotte Concentration Camp as Italian citizens, were released from Mauthausen. Until the end of January 1944 all the inmates from the concentration camp of Cairo Montenotte were released.

Among them was Alojz Kavčič, an employee at the Idrija Mercury Mine, a former internee at Cairo Montenotte Concentration Camp and at Mauthausen Concentration Camp who was close to Pirjevec. He kept a promise he gave to Pirjevec and immediately after his release in 1944 wrote a testimony in the form of a letter addressed to Karl Pirjevec, Avgust’s brother.

It took 29 years for the letter to become a public testimony, published in full in the Slovene TV 15 newspaper. Until then it was kept in the archives of the League of Communists of Slovenia. Today it is held in the Archives of Slovenia. The letter is not signed. The author didn’t sign it since at the time of their release from Mauthausen and its subsidiaries the internees received orders from the Gestapo not to reveal their concentration camp experiences.

In the letter Avgust Pirjevec is described as having been an important fatherly figure to the internees. He died on 19 December and was cremated in the concentration camp crematorium the next day together with 31 “companions”.

Details about the internment in Mauthausen

Avgust wrote home from Coroneo Prison that he was healthy and doing fine. On the contrary, both Avgust and Alojz were beaten during their interrogation in Trieste. Alojz informed Avgust’s brother that Avgust left the prison exhausted and weak.

In the letter little attention is paid to the internment in Cairo Montenotte. The testimony became more detailed when transport left the Fascist camp on 8 October. Initially, the internees who were crowded in cattle wagons were meant to arrive at Dachau. Due to lack of space the train was directed to Mauthausen, arriving there on 12 October. The next day a group of newly arrived internees walked to Gusen Concentration Camp.

Immediately they suffered humiliation and torture on the part of some Polish citizens (the guards of the barracks), described as extremely violent criminals. “For few days they were wildly violent. We were forced to stay partially naked in the open from morning till evening. They beat us relentlessly and mistreated us as much as they wanted. We were beaten with a truncheon for no reason and many times they would kick us mercilessly whilst we were lying on the ground.” After fourteen days of extreme violence and humiliation a group of internees was selected to work in a quarry, on construction sites for new barracks or on other kinds of manual works. “There we were literally slaves!”

From the beginning Avgust was appointed as chief interpreter. We are informed that he fell out of favour with the commander of a block and his subordinates.

Avgust’s relocation to the Kosten-Hofen quarry, organized by Czech inmates, didn’t change the situation. “Karl Fisher, a Polish gypsy, was a commander there, he and his German subordinate, Otto Vouchenig, couldn’t stand the deceased [meaning Avgust]”. For that reason Avgust was exposed to extreme verbal humiliation and physical violence. Even though he was an appointed translator, he worked and carried heavy blocks of stone.

One further relocation was organised to help Avgust, this time to the Steyr factory, today listed as an armaments plant, located within a concentration camp. “He was carrying heavy pieces of iron bars on a daily basis. That was too difficult for him. He was very weak,” Alojz wrote.

On 16 November, a commission from Berlin came to investigate the detention of those Italian internees who had arrived from Cairo Montenotte. “The [Italian] commander had insisted we Slovene and Croatian nationals be interned in Gusen because we had been caught in the woods as dangerous communists. (The commander's name was Passavanti)”, Kavčič wrote in his letter. On this occasion Avgust was appointed as a the commission's interpreter. He was very weak. He was standing in front of the commission for six, seven hours at a time during a period when camp meals had been reduced.

Kavčič reports that his hearing was on 7 December. “At that time he [Avgust Pirjevec] told me he was not well and was having trouble retaining liquids. I encouraged him not to give in[...] to try to hold out until we would be allocated to civilian work outside the camp.”

We learn that the first transfer of former Cairo Montenotte Concentration Camp internees took place on the same day. “In the commission’s opinion he was too weak to travel and he was kept in the camp.” Furthermore, Alojz wrote that the members of the first group of internees from Cairo Montenotte were appointed as air-raid wardens, part of the Fire Brigade in Linz. The second group was released on 14 December and directed to Linz. At the time Avgust was in a camp hospital. “The last consignment left on 24 January 1944- direction home!” Alojz wrote. The last trainload consisted of 360 internees, all skin and bone. According to Alojz, three died during the journey , and a lot more at home, having been introduced too early to large meals.

Relentless Atrocities

A meaningful part of the letter describes the control of lice. On a daily basis internees were ordered to undress and undergo a

tedious check for lice which regularly turned into a beating using truncheons.

It was not surprising that some lost consciousness as a result of pain. If lice were found, a prisoner's clothing and blankets were taken away from him as a lice prevention measure.

In such cases, if there was no solidarity, an exhausted and malnourished internee was left in the freezing cold throughout the winter night. There was no heating in the barracks, quite the opposite, the doors were left wide open. They had also daily hygiene controls. Violence was constant.

Over a 90 day period,the length of time the majority of internees spent in Mauthausen and Gusen, Kavčič reports 250 deaths among the 1250 Slovene and Croatian nationals who had been moved from the Italian Fascist Cairo Montenotte Concentration Camp for Civilians. Deaths occurred mostly due to beating and starvation.

The custodian of his memory

Alenka Pirjevec (1945), Dušan’s daughter and Avgust’s granddaughter, keeps his memory alive. Her grandmother, Zora, passed on to her the duty of remembering. “My grandmother told me a bit about him. I assume it was difficult for her to talk. Even my father didn’t talk much about him. I knew some superficial facts, no details,” Alenka told us. It was Anton Kavčič’s letter that brought to light Avgust Pirjevecì's life during his double internment and period of forced labour.

Sasa Petejan (2016)

The workers' re-education camps (AEL) were set up in 1940 by the Gestapo in order to re-educate individuals accused of acts of industrial sabotage or who, for some reason, were held to be “reluctant” to work. In effect, these camps were also a means of exploiting forced labour. It has been estimated that in Germany and the German-occupied territories around 200 Arbeitserziehungslager had been set up in which around 500,000 people had been imprisoned.

During the Second World War the Germans established prisoner of war units known as Bau-und Arbeits Battaillon (shortened to B.A.B.). The B.A.B. were made up on average of 600 prisoners of war who were used as forced labour. The distinguishing feature of these forced labour units was that they were mobile; unlike the prisoners who were being held in the Stalag, these workers were not stationed in a specific location but were moved around according to necessity.

The I.G. Farben Company was founded in 1925 from the merger of several different German industries. During the Second World War it was the main producer of chemicals for Nazi Germany. I.G. Farben made more use of forced labour than any other industry, particularly during the construction of the plants at Auschwitz. The directors of I.G. Farben were among the accused at the Nuremberg Trials of 1947/48. At the end of the war the decision was taken to split up the industry into its original component parts.

The Arbeitskommando were work camps detachments for prisoners who had been captured by the Germans. Usually made up of a few hundred prisoners, they were set up near to places of employment (factories, mines, agricultural establishments etc.). They were run from a central Stalag (prisoner of war camp), which may have been responsible for hundreds of work detachments. The work detachments for Allied prisoners of war were visited on a regular basis by representatives of the Red Cross.

The Military Work Inspectorate was set up in October 1943 with the aim of organising a workforce which was to construct territorial defences for the Italian Republic of Salò and repair the damage caused by air raids. Known as the “Organizzazione Paladino” (Paladino Organisation) after its founder and commanding officer, and operating in strict collaboration with, and at times directly employed by, the Germans, it took on several tens of thousands of workers.

The Todt Organisation was begun in Germany at the end of the 'Thirties with the aim of setting up a workforce which would build military defences. The idea of Fritz Todd, who was also its director until his death in 1942, during the war it exploited forced labour in German-occupied countries. In Italy it played a fundamental role in the construction of defences along the Appenines in support of the Wehrmacht, employing tens of thousands of men.

Born in Scilla (Reggio Calabria) in 1890, he volunteered for the Corps of Engineers as a telegraphist in 1907. In 1908 he rose to the rank of sergeant, a rank he held throughout the War in Libya. In 1914 he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and during the First World War he was made captain.

Afterwards he remained in the Armed Forces and in 1932 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1936 he took part in the War in Ethiopia, during which he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the Second World War, he returned to Italy after participating in the Greek campaign and was assigned to the Bolzano Corps. In 1942 he was promoted to brigader general. After the armistice he joined the Italian Social Republic for which he created the Military Labour Inspectorate.

He finally retired in 1945 and in 1970 he was awarded the honorary grade of major general.

He died in 1974.

Fritz Sauckel, born in 1894, was a local Nazi party official. In 1942 he was nominated plenipotentiary for the organisation of work throughout all the German-occupied territories. In practice, he was responsible for the compulsory engagement of forced labour. In Italy his organisation tried to round up hundreds of thousands of men to send to the German Reich, with scarce results. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to death, the sentence being carried out in 1946.

Albert Speer, born in 1905, was an architect who enjoyed an excellent personal relationship with Adolf Hitler. Even though he was not an ardent Nazi, he was the brains behind the staging of the Party parades, thereby assuring for himself the esteem and trust of the dictator. In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt, he was put in charge of the Ministry of Arms and Munitions, which oversaw the Todt organisation. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to twenty years imprisonment. He died in London in 1981.

A German prisoner of war camp. The living conditions in the Stalag varied considerably according to the nationality of the prisoners (Allied, Russian, Italian military internees, etc.)

Fritz Todt was a German engineer who was responsible, in the 'Thirties, for building the motorway system as desired by Hitler. At the end of the 'Thirties he set up the Todt Organisation, with the aim of supplying forced labour to be used in the building of defences along the French border. During the war his organisation oversaw the use of forced labour in the occupied territories. He died in a plane crash in 1942.

The Gemeinschaftslager, like the Wohnlager, were unsupervised camps for foreign workers, while the Arbeitslager were supervised. Generally speaking, the concept of forced labour is applied only to the latter, but at the present time historians are undoubtedly tending to review the concept of forced labour, extending it to include work situations which are apparently free but in reality are forced. More specifically, the current discussion tends to be orientated towards a concept of forced labour which includes these three distinctive elements:

- from a legal point of view, it is impossible for the worker to dissolve the relationship with his employer

- from the social point of view, the possibilities of significantly influencing employment conditions are limited

- there is a high mortality rate, which indicates a higher than average workload and a provision of means of sustenance below the necessary requirements.

See: [https://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/geschichte/auslaendisch/begriffe/index.html]

The workers' re-education camps (AEL) were set up in 1940 by the Gestapo in order to re-educate individuals accused of acts of industrial sabotage or who, for some reason, were held to be “reluctant” to work. In effect, these camps were also a means of exploiting forced labour. It has been estimated that in Germany and the German-occupied territories around 200 Arbeitserziehungslager had been set up in which around 500,000 people had been imprisoned.

During the Second World War the Germans established prisoner of war units known as Bau-und Arbeits Battaillon (shortened to B.A.B.). The B.A.B. were made up on average of 600 prisoners of war who were used as forced labour. The distinguishing feature of these forced labour units was that they were mobile; unlike the prisoners who were being held in the Stalag, these workers were not stationed in a specific location but were moved around according to necessity.

The I.G. Farben Company was founded in 1925 from the merger of several different German industries. During the Second World War it was the main producer of chemicals for Nazi Germany. I.G. Farben made more use of forced labour than any other industry, particularly during the construction of the plants at Auschwitz. The directors of I.G. Farben were among the accused at the Nuremberg Trials of 1947/48. At the end of the war the decision was taken to split up the industry into its original component parts.

The Arbeitskommando were work camps detachments for prisoners who had been captured by the Germans. Usually made up of a few hundred prisoners, they were set up near to places of employment (factories, mines, agricultural establishments etc.). They were run from a central Stalag (prisoner of war camp), which may have been responsible for hundreds of work detachments. The work detachments for Allied prisoners of war were visited on a regular basis by representatives of the Red Cross.

The Military Work Inspectorate was set up in October 1943 with the aim of organising a workforce which was to construct territorial defences for the Italian Republic of Salò and repair the damage caused by air raids. Known as the “Organizzazione Paladino” (Paladino Organisation) after its founder and commanding officer, and operating in strict collaboration with, and at times directly employed by, the Germans, it took on several tens of thousands of workers.

The Todt Organisation was begun in Germany at the end of the 'Thirties with the aim of setting up a workforce which would build military defences. The idea of Fritz Todd, who was also its director until his death in 1942, during the war it exploited forced labour in German-occupied countries. In Italy it played a fundamental role in the construction of defences along the Appenines in support of the Wehrmacht, employing tens of thousands of men.

Born in Scilla (Reggio Calabria) in 1890, he volunteered for the Corps of Engineers as a telegraphist in 1907. In 1908 he rose to the rank of sergeant, a rank he held throughout the War in Libya. In 1914 he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and during the First World War he was made captain.

Afterwards he remained in the Armed Forces and in 1932 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1936 he took part in the War in Ethiopia, during which he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the Second World War, he returned to Italy after participating in the Greek campaign and was assigned to the Bolzano Corps. In 1942 he was promoted to brigader general. After the armistice he joined the Italian Social Republic for which he created the Military Labour Inspectorate.

He finally retired in 1945 and in 1970 he was awarded the honorary grade of major general.

He died in 1974.

Fritz Sauckel, born in 1894, was a local Nazi party official. In 1942 he was nominated plenipotentiary for the organisation of work throughout all the German-occupied territories. In practice, he was responsible for the compulsory engagement of forced labour. In Italy his organisation tried to round up hundreds of thousands of men to send to the German Reich, with scarce results. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to death, the sentence being carried out in 1946.

Albert Speer, born in 1905, was an architect who enjoyed an excellent personal relationship with Adolf Hitler. Even though he was not an ardent Nazi, he was the brains behind the staging of the Party parades, thereby assuring for himself the esteem and trust of the dictator. In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt, he was put in charge of the Ministry of Arms and Munitions, which oversaw the Todt organisation. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to twenty years imprisonment. He died in London in 1981.

A German prisoner of war camp. The living conditions in the Stalag varied considerably according to the nationality of the prisoners (Allied, Russian, Italian military internees, etc.)

Fritz Todt was a German engineer who was responsible, in the 'Thirties, for building the motorway system as desired by Hitler. At the end of the 'Thirties he set up the Todt Organisation, with the aim of supplying forced labour to be used in the building of defences along the French border. During the war his organisation oversaw the use of forced labour in the occupied territories. He died in a plane crash in 1942.

The Gemeinschaftslager, like the Wohnlager, were unsupervised camps for foreign workers, while the Arbeitslager were supervised. Generally speaking, the concept of forced labour is applied only to the latter, but at the present time historians are undoubtedly tending to review the concept of forced labour, extending it to include work situations which are apparently free but in reality are forced. More specifically, the current discussion tends to be orientated towards a concept of forced labour which includes these three distinctive elements:

- from a legal point of view, it is impossible for the worker to dissolve the relationship with his employer

- from the social point of view, the possibilities of significantly influencing employment conditions are limited

- there is a high mortality rate, which indicates a higher than average workload and a provision of means of sustenance below the necessary requirements.

See: [https://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/geschichte/auslaendisch/begriffe/index.html]

The workers' re-education camps (AEL) were set up in 1940 by the Gestapo in order to re-educate individuals accused of acts of industrial sabotage or who, for some reason, were held to be “reluctant” to work. In effect, these camps were also a means of exploiting forced labour. It has been estimated that in Germany and the German-occupied territories around 200 Arbeitserziehungslager had been set up in which around 500,000 people had been imprisoned.

During the Second World War the Germans established prisoner of war units known as Bau-und Arbeits Battaillon (shortened to B.A.B.). The B.A.B. were made up on average of 600 prisoners of war who were used as forced labour. The distinguishing feature of these forced labour units was that they were mobile; unlike the prisoners who were being held in the Stalag, these workers were not stationed in a specific location but were moved around according to necessity.

The I.G. Farben Company was founded in 1925 from the merger of several different German industries. During the Second World War it was the main producer of chemicals for Nazi Germany. I.G. Farben made more use of forced labour than any other industry, particularly during the construction of the plants at Auschwitz. The directors of I.G. Farben were among the accused at the Nuremberg Trials of 1947/48. At the end of the war the decision was taken to split up the industry into its original component parts.

The Arbeitskommando were work camps detachments for prisoners who had been captured by the Germans. Usually made up of a few hundred prisoners, they were set up near to places of employment (factories, mines, agricultural establishments etc.). They were run from a central Stalag (prisoner of war camp), which may have been responsible for hundreds of work detachments. The work detachments for Allied prisoners of war were visited on a regular basis by representatives of the Red Cross.

The Military Work Inspectorate was set up in October 1943 with the aim of organising a workforce which was to construct territorial defences for the Italian Republic of Salò and repair the damage caused by air raids. Known as the “Organizzazione Paladino” (Paladino Organisation) after its founder and commanding officer, and operating in strict collaboration with, and at times directly employed by, the Germans, it took on several tens of thousands of workers.

The Todt Organisation was begun in Germany at the end of the 'Thirties with the aim of setting up a workforce which would build military defences. The idea of Fritz Todd, who was also its director until his death in 1942, during the war it exploited forced labour in German-occupied countries. In Italy it played a fundamental role in the construction of defences along the Appenines in support of the Wehrmacht, employing tens of thousands of men.

Born in Scilla (Reggio Calabria) in 1890, he volunteered for the Corps of Engineers as a telegraphist in 1907. In 1908 he rose to the rank of sergeant, a rank he held throughout the War in Libya. In 1914 he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and during the First World War he was made captain.

Afterwards he remained in the Armed Forces and in 1932 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1936 he took part in the War in Ethiopia, during which he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the Second World War, he returned to Italy after participating in the Greek campaign and was assigned to the Bolzano Corps. In 1942 he was promoted to brigader general. After the armistice he joined the Italian Social Republic for which he created the Military Labour Inspectorate.

He finally retired in 1945 and in 1970 he was awarded the honorary grade of major general.

He died in 1974.

Fritz Sauckel, born in 1894, was a local Nazi party official. In 1942 he was nominated plenipotentiary for the organisation of work throughout all the German-occupied territories. In practice, he was responsible for the compulsory engagement of forced labour. In Italy his organisation tried to round up hundreds of thousands of men to send to the German Reich, with scarce results. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to death, the sentence being carried out in 1946.

Albert Speer, born in 1905, was an architect who enjoyed an excellent personal relationship with Adolf Hitler. Even though he was not an ardent Nazi, he was the brains behind the staging of the Party parades, thereby assuring for himself the esteem and trust of the dictator. In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt, he was put in charge of the Ministry of Arms and Munitions, which oversaw the Todt organisation. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to twenty years imprisonment. He died in London in 1981.

Fritz Todt was a German engineer who was responsible, in the 'Thirties, for building the motorway system as desired by Hitler. At the end of the 'Thirties he set up the Todt Organisation, with the aim of supplying forced labour to be used in the building of defences along the French border. During the war his organisation oversaw the use of forced labour in the occupied territories. He died in a plane crash in 1942.

The workers' re-education camps (AEL) were set up in 1940 by the Gestapo in order to re-educate individuals accused of acts of industrial sabotage or who, for some reason, were held to be “reluctant” to work. In effect, these camps were also a means of exploiting forced labour. It has been estimated that in Germany and the German-occupied territories around 200 Arbeitserziehungslager had been set up in which around 500,000 people had been imprisoned.

During the Second World War the Germans established prisoner of war units known as Bau-und Arbeits Battaillon (shortened to B.A.B.). The B.A.B. were made up on average of 600 prisoners of war who were used as forced labour. The distinguishing feature of these forced labour units was that they were mobile; unlike the prisoners who were being held in the Stalag, these workers were not stationed in a specific location but were moved around according to necessity.

The I.G. Farben Company was founded in 1925 from the merger of several different German industries. During the Second World War it was the main producer of chemicals for Nazi Germany. I.G. Farben made more use of forced labour than any other industry, particularly during the construction of the plants at Auschwitz. The directors of I.G. Farben were among the accused at the Nuremberg Trials of 1947/48. At the end of the war the decision was taken to split up the industry into its original component parts.

The Arbeitskommando were work camps detachments for prisoners who had been captured by the Germans. Usually made up of a few hundred prisoners, they were set up near to places of employment (factories, mines, agricultural establishments etc.). They were run from a central Stalag (prisoner of war camp), which may have been responsible for hundreds of work detachments. The work detachments for Allied prisoners of war were visited on a regular basis by representatives of the Red Cross.

The Military Work Inspectorate was set up in October 1943 with the aim of organising a workforce which was to construct territorial defences for the Italian Republic of Salò and repair the damage caused by air raids. Known as the “Organizzazione Paladino” (Paladino Organisation) after its founder and commanding officer, and operating in strict collaboration with, and at times directly employed by, the Germans, it took on several tens of thousands of workers.

The Todt Organisation was begun in Germany at the end of the 'Thirties with the aim of setting up a workforce which would build military defences. The idea of Fritz Todd, who was also its director until his death in 1942, during the war it exploited forced labour in German-occupied countries. In Italy it played a fundamental role in the construction of defences along the Appenines in support of the Wehrmacht, employing tens of thousands of men.

Born in Scilla (Reggio Calabria) in 1890, he volunteered for the Corps of Engineers as a telegraphist in 1907. In 1908 he rose to the rank of sergeant, a rank he held throughout the War in Libya. In 1914 he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and during the First World War he was made captain.

Afterwards he remained in the Armed Forces and in 1932 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1936 he took part in the War in Ethiopia, during which he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the Second World War, he returned to Italy after participating in the Greek campaign and was assigned to the Bolzano Corps. In 1942 he was promoted to brigader general. After the armistice he joined the Italian Social Republic for which he created the Military Labour Inspectorate.

He finally retired in 1945 and in 1970 he was awarded the honorary grade of major general.

He died in 1974.

Fritz Sauckel, born in 1894, was a local Nazi party official. In 1942 he was nominated plenipotentiary for the organisation of work throughout all the German-occupied territories. In practice, he was responsible for the compulsory engagement of forced labour. In Italy his organisation tried to round up hundreds of thousands of men to send to the German Reich, with scarce results. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to death, the sentence being carried out in 1946.

Albert Speer, born in 1905, was an architect who enjoyed an excellent personal relationship with Adolf Hitler. Even though he was not an ardent Nazi, he was the brains behind the staging of the Party parades, thereby assuring for himself the esteem and trust of the dictator. In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt, he was put in charge of the Ministry of Arms and Munitions, which oversaw the Todt organisation. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to twenty years imprisonment. He died in London in 1981.

Fritz Todt was a German engineer who was responsible, in the 'Thirties, for building the motorway system as desired by Hitler. At the end of the 'Thirties he set up the Todt Organisation, with the aim of supplying forced labour to be used in the building of defences along the French border. During the war his organisation oversaw the use of forced labour in the occupied territories. He died in a plane crash in 1942.

/01_Avgust-Pirjevec_Portrait_Before-Arrest1.jpg)

/03a_03bAvgust_Pirjevec_Letter_180543a.jpg)