The organisation of forced labour in Italy (1943-1945)

German agencies for the exploitation of forced labour in Italy in the autumn of 1943

The occupation of the Italian peninsula between 9 and 10 September on the part of the Wehrmacht represented a great opportunity for the latter to lay hands on millions of workers.

About 800,000 servicemen ended up in the hands of the army, which transferred them to camps in Germany and Poland whilst deciding what to do with them. Moreover, during the first few weeks of the occupation, in the power vacuum left by the collapse of the Kingdom of Italy and the lack of a collaborationist government (Mussolini was in German hands in that country until 23 September), it was the Wehrmacht which was the de facto government in the occupied territory.

In theory, on 10 September 1943 the German ambassador Rudolph Rahn had been entrusted with civil powers in Italy by means of an order emitted by the Führer. With this order the National Fascist Government (as the occupied territory was called at the time, given that there was in fact no real Italian government) was officially recognised by the Reich, thereby guaranteeing control over the new fascist state through the offices of the plenipotentiary in Italy, Rahn.1 Theoretically Rahn had the powers to govern Italy through the prefects, who would have had to carry out the instructions handed down via his subordinates.

Nevertheless, just a few days later the military also set up their own administration. The Chief of Staff of the Wehrmacht, Wilhelm Keitel, gave orders for the establishment of a territorial administration in the whole of the occupied zone, to be run by military garrisons in the major cities and police stations in the smaller ones. These forces were required to work alongside the existing Italian authorities. On 14 September General Rudolf Toussaint was appointed commander of the Military Control Board. From the beginning of October Toussaint created a series of local garrisons, the Militärkommandanturen, which were to exercise control over areas roughly corresponding to the provinces. The head of the Military Control Board became the chief German controller in Italy, with the remit to “operate to all effects as a Control Board where the independent Italian government was concerned, both at constitutional and international levels.”2

However Toussaint had no control over those territories which had been annexed “de facto” by the Reich, that is the “operational zones of the Pre-Alps and the Adriatic Littoral”, a group of provinces which on 11 September had been placed under the control of two Gauleiters (local fascist party chiefs), Franz Hofer and Friederich Rainer. Both the Italian authorities and military authorities were excluded from these two “operational zones”.

Moreover, from 10 October 1943 onwards the provinces to the south of Rome were assigned to Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, the Supreme Commander of the Southern Front, who had the power to issue orders both in civil and military fields.

In addition to the Wehrmacht and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, all the other German political and economic institutions established themselves in Italy, for example there was a representative of the Goering's Four Year Plan, an envoy from Speer's Ministry of Arms and Munitions (hence the Todt) and an envoy from the organisation run by Sauckel, the “ Plenipotentiary for the workforce”. All three organisations were competing amongst themselves for the recruitment of forced labour.

This multiplicity of organisations, apparently in contradiction amongst themselves, created a state of general chaos, thus adding to the total confusion which reigned during the weeks immediately following the occupation due to the absence of an Italian government and of institutions to which the Italian citizens could turn with certainty. Which orders, which laws and which institutions should they obey?

For example, on 16 September the Headquarters of the Armed Forces of the Reich, as occupiers of the city of Milan, brought out an 11-point article in the daily newspaper “Il Corriere della Sera”: “1) The factories in the zone of Upper Italy occupied by the Armed Forces of the Reich come under German law as far as the war effort is concerned. 2) All industrial and commercial enterprises must immediately recommence their activity. 3) All those firms in Upper Italy which have more than 1,000 or more employees must report to the Commercial Offices of the German Consulate General, which is temporarily situated in the Principe di Savoia hotel in Milan, in order to collect a questionnaire. 4) An inventory must be made immediately of all stocks of raw materials, half-finished and finished products which must then be consigned to the Commercial Offices of the German Consulate within ten days of the receipt of the aforesaid questionnaire and in any case not later than 30 September 1943. 5) The aforesaid firms will also indicate how many days' supply of fuel they are currently holding, what is their daily consumption and who is their usual supplier. […] 8) All managing directors of industrial establishments will have their position confirmed by the German Consulate General. They will be personally responsible for the running of the establishment with which they have been entrusted.3

Hence a military command had been put into operation by the Consulate General, a classic case of confusion between civil and military powers.

In this very early period, however, it was the Wehrmacht which carried most weight where the exploitation of forced labour was concerned. In September the German strategy was to use those men who had been rounded up in the zones near to the front line to build the fortifications needed to stop the Allied advance. Moreover, it seemed to be easier to convince the workers to enrol, or at least not to go into hiding, if they were employed near to their own homes and at the end, bearing in mind the fact that the Wehrmacht had taken around 800,000 prisoners from the Italian military, transferring them to camps in Germany and Poland, these civilians were of more use in the Peninsula than in the Reich. Ultimately, it is also necessary to bear in mind that while the army had a massive presence in Italy, the other German agencies needed time to transfer their offices and representatives to Italy and to organise their networks south of the Alps.

On 17 September Keitel issued a strict order in which the commanders of the German troops in Italy were invited to go on the hunt for workers. To carry out this order Keitel had "given them a free hand to take all necessary measures

Following on from these orders, and in anticipation of an evacuation of Southern Italy due to the Allied advance, the XIV German Panzerkorps, based in the Naples area, began to undertake a series of operations to “hunt down slaves”, according to the terminology used by the Wehrmacht. Between 20 and 27 September German troops rounded up 18,000 men, whom they sent to transit camps, to be used as forced labour.5

These round-ups in the city of Naples, as is well known, had an unexpected outcome. The extremely rough measures adopted by the Wehrmacht led to a general uprising in the city and forced the German troops to withdraw in haste.

The city of Naples was not the only one to have been affected by roughly conducted round-ups during this early period of the occupation.

On 22 September Kesselring ordered the evacuation of the western coastal strip between Naples and Leghorn for a distance of five kilometres inland. Moreover, the evacuees would also have been forced into building fortifications. On 4 October the XIV Panzerkorps ordered the evacuation of the area between the front line and five kilometres to the north of it, again with the same intention of using male evacuees to build fortifications.

Between September and October all the areas of central Italy, Lazio, Marche and Abruzzo, were subjected to these evacuation orders and the rounding up of men for forced labour. By 10 November 35,000 civilians had been evacuated solely from the zone occupied by the XIV Panzerkorps.6

Numerous reports came in from the Italian authorities regarding the extremely rough methods used in carrying out these orders. For example, on 13 October 1943 the German unit based at Ariccia arrested an imprecise number of civilians, sending them firstly to the concentration camp at Bracciano and then to the one at Ostia.

Such methods did not change throughout the entire period of occupation. On 1 May, according to the Prefect of Rome, “German units, acting under superior orders, went into the Commune of Jenne (Province of Rome) to round up British prisoners who had escaped from prisoner of war camps. In the space of half an hour the entire population was assembled near the cemetery, to where the local company of the G.N.R. (National Republican Guard) and its commanding officer had been ordered to report. Towards 6 o'clock in the evening the majority of people were sent home but seven youngsters, with ages ranging from 18 to 21 years, were detained by the G.N.R., who the following morning arranged for them to be sent to Subiaco and handed over to the 107 Engineering Works Battalion, which accepted them into their ranks.7

In the autumn of 1943 the Germans tried to persuade the Italian authorities to collaborate. On 18 September Colonel Montezemolo, leader of the Italian Armed Forces in the “Open City”of Rome, was invited by the officer in charge of the city, General Rainer Stahel, to attend a meeting at which “the question of workers' battalions” was to be discussed.8

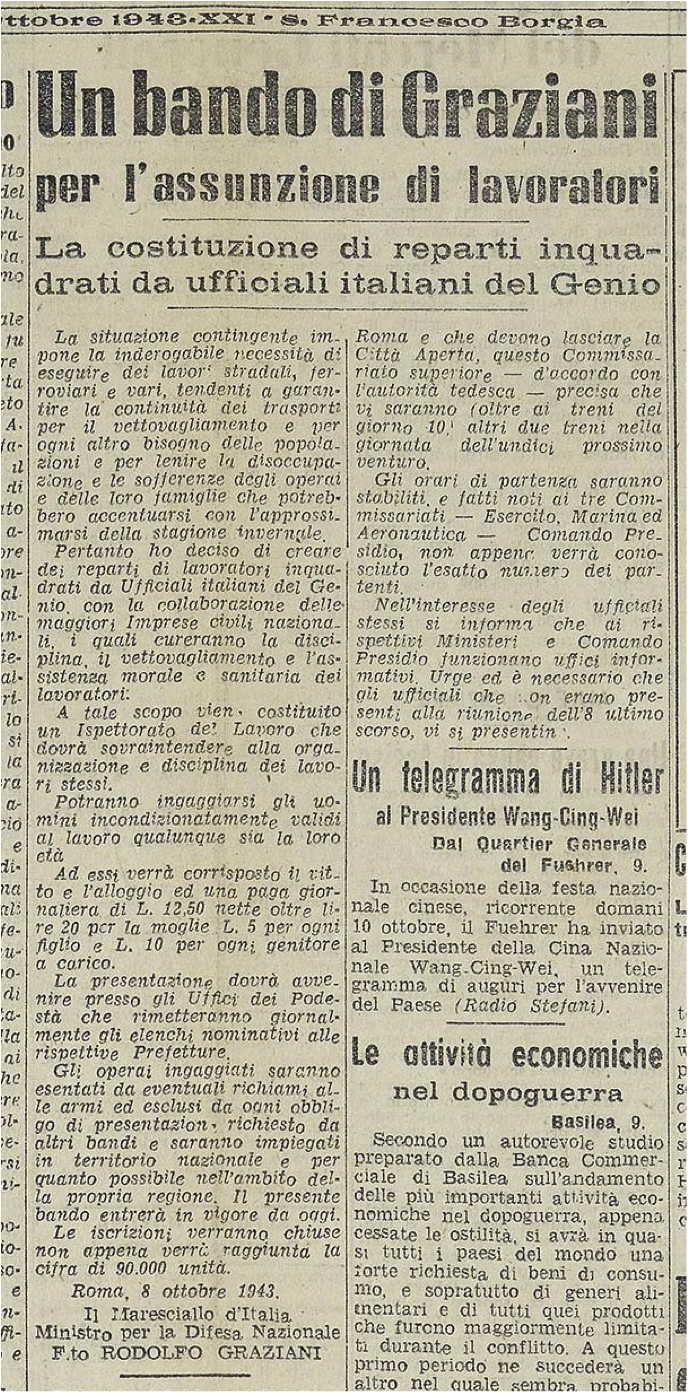

On 20 September the Southern High Command of the Wehrmacht created an office specifically “for the employment of Italian labour”, under the command of of Colonel Zimmermann. This office was meant to collaborate with the Italian prefects to create work units composed of around 60,000 men. The units were to have been put at the disposition of the various military units belonging to the Wehrmacht, and were to have been made up of 18 to 21-year-olds, specifically recruited by the same prefects. These 60,000 workers were to have been called up in three successive phases until the agreed number had been arrived at. When the prefects failed to obey these instructions, Kesselring threatened the civil population with round-ups and heavy fines.9

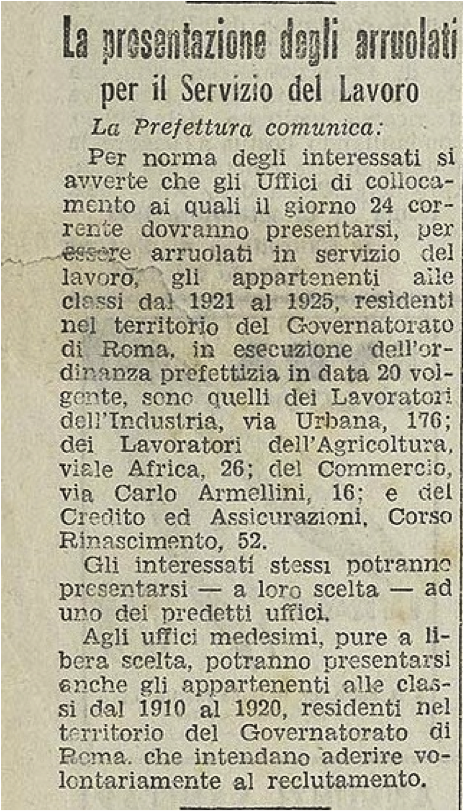

On 22 September the Prefect of Rome, Di Suni, announced the call-up for forced labour of all those youngsters aged between 18 and 21 years in the central Italian provinces. Payment was fixed at eight lire per day, with free board and lodgings. Other than their own pay, their family was to be 20 lire for their spouse, 10 lire for each parent for whom they were responsible and 5 lire for each child. Every worker had to report for duty with a blanket, a change of underwear, shoes, crockery and cutlery. Those who did not conform to regulations were to be punished according to what had been laid down in Royal Decree no. 1611, which dated back to 31 October 1942.

The response was disappointing: on 26 September 1943 Kesselring himself wrote to the Italian Home Office, which at the time was being run by a commissioner, complaining that despite the fact that the “orders” were very clear, “on 25 September the workforce as laid down in the agreed terms was not forthcoming.” As a result Kesselring requested that the number of workers be increased by 30,000.10

The Italian ministry replied by means of a long report which explained why such a disappointing result had been obtained. “The announcement came too soon after the painful events which had taken place between 9 and 12 September and the consequent general disorientation brought about by the hasty dissolution of the Italian Army.

In many areas the large number of incidents provoked by the German troops had terrorised the local population. The requisition of all types of material and in particular of motor vehicles and fuel, even from the Prefectures, the interruptions to telegram and telephone services and also to the railways, and the disarming of the Carabinieri and local police forces in many areas, had brought about such a state of disorganisation in the provinces as to create extreme difficulties for the Prefects in their attempts to publicise the call-up and carry out the recruitment, even under force. The belief that once enrolled the workers would be sent into combat zones or to Germany, or even to Poland or to Russia, ensured that large numbers of those belonging to the designated age groups left home and went into hiding. Enrolment into the ranks of the M.V.S.N. (Voluntary National Militia), and the enlistment of workers for Germany at a high level of remuneration, was taking place at the same time. The proposed pay is clearly insufficient to satisfy normal requirements, especially for those with a family to provide for.”11

In short, the Italian response to the Germans was to rebuke them, firstly for having created the chaos and having terrorised the population, and secondly for having requested that voluntary enrolment be organised by those Italian institutions from which they had taken away the means to carry out what had been asked of them. The result was that instead of the 60,000 labourers requested, 3,020 had enrolled voluntarily and 4,157 had been press-ganged by the Germans.

In the days which followed, attempts by the Italian authorities to use force were a fiasco. On 30 September the headquarters of the Italian Armed Forces in the “Open City” of Rome12 had carried out some round-ups - in city centre restaurants, on trains awaiting departure and also in the Registry Office - but in total they only managed to apprehend 21 people.13

These were obviously servicemen who had avoided the round-ups which had taken place immediately after the occupation at the instigation of the Wehrmacht, or were youngsters who had failed to respond to the call-up.

In the days which followed, between 24 September and 4 October, 16,000 men were interviewed of whom 11,325 were handed back to the Italians due to their being indispensable to the war effort, 3,577 were turned down for health reasons and 936 effectively taken on.14

Faced with such a humiliating failure, the German military decided to use force, and in Rome there were a number of indiscriminate round-ups (27 October 1943), which led to growing diffidence amongst the population as far as the Germans and their “brotherhood of workers” were concerned.

In a letter dated 19 November addressed to the Italian Home Office by Colonel Seifahrt, chief administrator of the Southern High Command of the Wehrmacht, it was proposed that ration books should be taken away from those youngsters who were evading work.

On 20 November General Francesco Paladino, who in the meantime had set up a General Labour Inspectorate about which more will be said later, went up to Gargnano for a personal meeting with Mussolini in the company of a “German General who is an expert on work service”, whose particulars are not known but who may have been Colonel Seifahrt himself.

It is highly likely that Mussolini wanted to know more about the work of the Inspectorate and its relationship with the German organisations. During this meeting the idea of taking away ration books from those who did not report to the Labour Inspectorate or the Todt was discussed and received Mussolini's wholehearted approval. “The representative of the Labour Inspectorate has revealed that the the enrolment of workers for this Inspectorate has not produced the desired results: it has therefore become necessary to implement without delay the decisions taken at the previous meeting: the supplements already agreed upon should be given to the workers and only to the workers. At a later time provisions will be made to give these supplements also to their families, as well as taking away the ration books from those who are not working and also from their families. It should be remembered that the DUCE, to whom this proposal was put on 21 November last, has given it his full approval, adding that at the present time in the Nation there should only be two categories of Italians: those in uniform and those in work.”15

On 29 November a further meeting took place at the German Embassy in Rome. The military commander of the city of Rome Kurt Mälzer, Colonel Seifahrt and the German Consul Eitel Möllhause were all in attendance as were Coriolano Pagnozzi, Tullio Tamburini (Chief of Police), Colonel Bocca (General Secretary of the Armed Forces), the Prefect of Rome, Vittorio Rolandi Ricci and a colonel representing General Francesco Paladino. The Italian contingent was compelled to listen to a furious outburst from Möllhausen, who said that whilst the German soldiers were out there fighting the “Italian youth was literally doing nothing”. At that point Rolandi Ricci proposed to take away the ration books from those youngsters who had not responded to the labour call-up and also from their families. Möllhausen gave his approval to this proposal and on 1 December, in the Prefecture, there was a further meeting at which only the Italians were present. In this meeting it was decided that the taking away of ration books would apply only to the citizens of Rome.

On 9 December a decree was passed stating that all Romans must report for forced labour, and failure to do so would result in the loss of their ration books. In the run-up to Christmas a register was started of men eligible for work and this new census was intended to be completed by 31 December.16 As is well known, this census di not produce the desired results.

In addition to the Wehrmacht, Fritz Sauckel's organisation also tried to get hold of Italian workers with the intention, however, of sending them to Germany. Between the end of September and the beginning of October, especially in Rome, a propaganda campaign was aimed at encouraging voluntary enrolment, with a proclamation from Kesselring himself directed at “The Italian Workers”: “In the past few days many Italian workers who had already been employed in Germany and who used to return to Italy for their holidays have applied to the German offices in Rome for permission to return to their old employment. They have taken the opportunity to make clear their desire to return to a more orderly way of life. They know that in Germany, where national socialism really does exist, and where at the present time a struggle of gigantic proportions is under way for a new Europe, they had been treated fairly and had received a just reward for their labours, so as to guarantee a good standard of living for them and their families. All these workers may now, as is their wish, return to Germany. Moreover, those who have not already been working in Germany may also apply to be employed there, either in industry or agriculture. They will receive the same treatment as those Italians who have already found work and sustenance beyond the Alps, with the same spirit of fairness and national socialism which now differentiates the New Germany from other nations. They will live amongst their German counterparts and those millions of free workers from all over our continent, enjoying that self-same common good which one day will be the foundation stone of the New Europe of industrial workers and farm labourers. Italian workers, apply for free work in Germany as hundreds of thousands of others have done before you. Report to the Recruitment Office in Via Tasso, number 155. There you will receive a German entry permit which will also give you free rail travel. You will not need to have an Italian passport or permission to leave Italy. You will be going to Germany as free workers and you will return as such to your country of birth".17

In the autumn of 1943, as can be seen, the situation was extremely confused. In Rome, for example, the recruitment offices of the Todt, the Sauckel Organisation and the Italian Paladino Organisation were all in the same building in Piazza dell’Esquilino. The unemployed workers were sent for and asked if they were willing to go to Germany. If they accepted they were sent to the Sauckel office, if they declined they were sent to the offices of the Todt or those of the Paladino Organisation.18

The attempt to convince the workers to enrol voluntarily ended in a fiasco. In Rome, out of the 100,000 unemployed, who according to the Fascist party lived in the capital and were in theory available for work, only one thousand turned up to enrol over the space of twelve days.

Obviously this type of political initiative was ineffectual, and even if some Wehrmacht officials carried on rounding up men and forcing them to build fortifications, the higher German authorities realised fairly early on that it was necessary to use the remaining Italian authorities and the newborn republican fascism to recruit the workforce needed to sustain the war effort.

On 1 October 1943 the plenipotentiary Rahn met Rommel and Toussaint on Lake Garda. At this meeting it was decided to use the republican government to run civil affairs.19 In this framework the newly-constituted RSI (Repubblica Sociale Italiana - Italian Social Republic) would legalise the recruitment of workers, including forced labourers, in such a way as to reassure the workers themselves.

At the same time, however, even the high-up fascist authorities realised that indiscriminate round-ups, forced labour and deportation to Germany would be a death blow to the prestige enjoyed by Fascism and the Republic. No one would have any confidence in a state which could not even guarantee minimum standards of personal security to its own citizens.

Note 1

Lutz Klinkhammer, L’occupazione tedesca in Italia, Bollati Boringhieri, Torino, 1997, pp.51-53.

Note 2

Lutz Klinkhammer, L’occupazione tedesca in Italia, Bollati Boringhieri, Torino, 1997, p. 62.

Note 3

“Corriere della Sera”, 16 settembre 1943.

Lutz Klinkhammer, L’occupazione tedesca in Italia, cit., p.131.

Note 5

Lutz Klinkhammer, L’occupazione tedesca in Italia, cit., p.132.

Note 6

Lutz Klinkhammer, L’occupazione tedesca in Italia, cit., p.136.

Note 7

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Segreteria particolare del Capo della Polizia RSI, b.35

Note 8

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Segreteria particolare del Capo della Polizia RSI, b.27.

Note 9

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Segreteria particolare del Capo della Polizia RSI, b.27

Note 10

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Segreteria particolare del Capo della Polizia RSI, b.27.

Note 11

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Segreteria particolare del Capo della Polizia RSI, b.27

Declared by both sides to be outside the war zone (translator's note)

Note 13

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Segreteria particolare del Capo della Polizia RSI, b.27.

Note 14

Lutz Klinkhammer, L’occupazione tedesca in Italia, cit., pp.138-139.

Note 15

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Segreteria particolare del Capo della Polizia RSI, b.27.

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Segreteria particolare del Capo della Polizia RSI, b.27.

Note 17

“Il Messaggero”, 21 settembre 1943.

Note 18

Lutz Klinkhammer, L’occupazione tedesca in Italia, cit., p.146.

Note 19

Lutz Klinkhammer, L’occupazione tedesca in Italia, cit., p.142

The workers' re-education camps (AEL) were set up in 1940 by the Gestapo in order to re-educate individuals accused of acts of industrial sabotage or who, for some reason, were held to be “reluctant” to work. In effect, these camps were also a means of exploiting forced labour. It has been estimated that in Germany and the German-occupied territories around 200 Arbeitserziehungslager had been set up in which around 500,000 people had been imprisoned.

During the Second World War the Germans established prisoner of war units known as Bau-und Arbeits Battaillon (shortened to B.A.B.). The B.A.B. were made up on average of 600 prisoners of war who were used as forced labour. The distinguishing feature of these forced labour units was that they were mobile; unlike the prisoners who were being held in the Stalag, these workers were not stationed in a specific location but were moved around according to necessity.

The I.G. Farben Company was founded in 1925 from the merger of several different German industries. During the Second World War it was the main producer of chemicals for Nazi Germany. I.G. Farben made more use of forced labour than any other industry, particularly during the construction of the plants at Auschwitz. The directors of I.G. Farben were among the accused at the Nuremberg Trials of 1947/48. At the end of the war the decision was taken to split up the industry into its original component parts.

The Arbeitskommando were work camps detachments for prisoners who had been captured by the Germans. Usually made up of a few hundred prisoners, they were set up near to places of employment (factories, mines, agricultural establishments etc.). They were run from a central Stalag (prisoner of war camp), which may have been responsible for hundreds of work detachments. The work detachments for Allied prisoners of war were visited on a regular basis by representatives of the Red Cross.

The Military Work Inspectorate was set up in October 1943 with the aim of organising a workforce which was to construct territorial defences for the Italian Republic of Salò and repair the damage caused by air raids. Known as the “Organizzazione Paladino” (Paladino Organisation) after its founder and commanding officer, and operating in strict collaboration with, and at times directly employed by, the Germans, it took on several tens of thousands of workers.

The Todt Organisation was begun in Germany at the end of the 'Thirties with the aim of setting up a workforce which would build military defences. The idea of Fritz Todd, who was also its director until his death in 1942, during the war it exploited forced labour in German-occupied countries. In Italy it played a fundamental role in the construction of defences along the Appenines in support of the Wehrmacht, employing tens of thousands of men.

Born in Scilla (Reggio Calabria) in 1890, he volunteered for the Corps of Engineers as a telegraphist in 1907. In 1908 he rose to the rank of sergeant, a rank he held throughout the War in Libya. In 1914 he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and during the First World War he was made captain.

Afterwards he remained in the Armed Forces and in 1932 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1936 he took part in the War in Ethiopia, during which he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the Second World War, he returned to Italy after participating in the Greek campaign and was assigned to the Bolzano Corps. In 1942 he was promoted to brigader general. After the armistice he joined the Italian Social Republic for which he created the Military Labour Inspectorate.

He finally retired in 1945 and in 1970 he was awarded the honorary grade of major general.

He died in 1974.

Fritz Sauckel, born in 1894, was a local Nazi party official. In 1942 he was nominated plenipotentiary for the organisation of work throughout all the German-occupied territories. In practice, he was responsible for the compulsory engagement of forced labour. In Italy his organisation tried to round up hundreds of thousands of men to send to the German Reich, with scarce results. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to death, the sentence being carried out in 1946.

Albert Speer, born in 1905, was an architect who enjoyed an excellent personal relationship with Adolf Hitler. Even though he was not an ardent Nazi, he was the brains behind the staging of the Party parades, thereby assuring for himself the esteem and trust of the dictator. In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt, he was put in charge of the Ministry of Arms and Munitions, which oversaw the Todt organisation. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to twenty years imprisonment. He died in London in 1981.

A German prisoner of war camp. The living conditions in the Stalag varied considerably according to the nationality of the prisoners (Allied, Russian, Italian military internees, etc.)

Fritz Todt was a German engineer who was responsible, in the 'Thirties, for building the motorway system as desired by Hitler. At the end of the 'Thirties he set up the Todt Organisation, with the aim of supplying forced labour to be used in the building of defences along the French border. During the war his organisation oversaw the use of forced labour in the occupied territories. He died in a plane crash in 1942.

The Gemeinschaftslager, like the Wohnlager, were unsupervised camps for foreign workers, while the Arbeitslager were supervised. Generally speaking, the concept of forced labour is applied only to the latter, but at the present time historians are undoubtedly tending to review the concept of forced labour, extending it to include work situations which are apparently free but in reality are forced. More specifically, the current discussion tends to be orientated towards a concept of forced labour which includes these three distinctive elements:

- from a legal point of view, it is impossible for the worker to dissolve the relationship with his employer

- from the social point of view, the possibilities of significantly influencing employment conditions are limited

- there is a high mortality rate, which indicates a higher than average workload and a provision of means of sustenance below the necessary requirements.

See: [https://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/geschichte/auslaendisch/begriffe/index.html]

The workers' re-education camps (AEL) were set up in 1940 by the Gestapo in order to re-educate individuals accused of acts of industrial sabotage or who, for some reason, were held to be “reluctant” to work. In effect, these camps were also a means of exploiting forced labour. It has been estimated that in Germany and the German-occupied territories around 200 Arbeitserziehungslager had been set up in which around 500,000 people had been imprisoned.

During the Second World War the Germans established prisoner of war units known as Bau-und Arbeits Battaillon (shortened to B.A.B.). The B.A.B. were made up on average of 600 prisoners of war who were used as forced labour. The distinguishing feature of these forced labour units was that they were mobile; unlike the prisoners who were being held in the Stalag, these workers were not stationed in a specific location but were moved around according to necessity.

The I.G. Farben Company was founded in 1925 from the merger of several different German industries. During the Second World War it was the main producer of chemicals for Nazi Germany. I.G. Farben made more use of forced labour than any other industry, particularly during the construction of the plants at Auschwitz. The directors of I.G. Farben were among the accused at the Nuremberg Trials of 1947/48. At the end of the war the decision was taken to split up the industry into its original component parts.

The Arbeitskommando were work camps detachments for prisoners who had been captured by the Germans. Usually made up of a few hundred prisoners, they were set up near to places of employment (factories, mines, agricultural establishments etc.). They were run from a central Stalag (prisoner of war camp), which may have been responsible for hundreds of work detachments. The work detachments for Allied prisoners of war were visited on a regular basis by representatives of the Red Cross.

The Military Work Inspectorate was set up in October 1943 with the aim of organising a workforce which was to construct territorial defences for the Italian Republic of Salò and repair the damage caused by air raids. Known as the “Organizzazione Paladino” (Paladino Organisation) after its founder and commanding officer, and operating in strict collaboration with, and at times directly employed by, the Germans, it took on several tens of thousands of workers.

The Todt Organisation was begun in Germany at the end of the 'Thirties with the aim of setting up a workforce which would build military defences. The idea of Fritz Todd, who was also its director until his death in 1942, during the war it exploited forced labour in German-occupied countries. In Italy it played a fundamental role in the construction of defences along the Appenines in support of the Wehrmacht, employing tens of thousands of men.

Born in Scilla (Reggio Calabria) in 1890, he volunteered for the Corps of Engineers as a telegraphist in 1907. In 1908 he rose to the rank of sergeant, a rank he held throughout the War in Libya. In 1914 he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and during the First World War he was made captain.

Afterwards he remained in the Armed Forces and in 1932 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1936 he took part in the War in Ethiopia, during which he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the Second World War, he returned to Italy after participating in the Greek campaign and was assigned to the Bolzano Corps. In 1942 he was promoted to brigader general. After the armistice he joined the Italian Social Republic for which he created the Military Labour Inspectorate.

He finally retired in 1945 and in 1970 he was awarded the honorary grade of major general.

He died in 1974.

Fritz Sauckel, born in 1894, was a local Nazi party official. In 1942 he was nominated plenipotentiary for the organisation of work throughout all the German-occupied territories. In practice, he was responsible for the compulsory engagement of forced labour. In Italy his organisation tried to round up hundreds of thousands of men to send to the German Reich, with scarce results. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to death, the sentence being carried out in 1946.

Albert Speer, born in 1905, was an architect who enjoyed an excellent personal relationship with Adolf Hitler. Even though he was not an ardent Nazi, he was the brains behind the staging of the Party parades, thereby assuring for himself the esteem and trust of the dictator. In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt, he was put in charge of the Ministry of Arms and Munitions, which oversaw the Todt organisation. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to twenty years imprisonment. He died in London in 1981.

A German prisoner of war camp. The living conditions in the Stalag varied considerably according to the nationality of the prisoners (Allied, Russian, Italian military internees, etc.)

Fritz Todt was a German engineer who was responsible, in the 'Thirties, for building the motorway system as desired by Hitler. At the end of the 'Thirties he set up the Todt Organisation, with the aim of supplying forced labour to be used in the building of defences along the French border. During the war his organisation oversaw the use of forced labour in the occupied territories. He died in a plane crash in 1942.

The Gemeinschaftslager, like the Wohnlager, were unsupervised camps for foreign workers, while the Arbeitslager were supervised. Generally speaking, the concept of forced labour is applied only to the latter, but at the present time historians are undoubtedly tending to review the concept of forced labour, extending it to include work situations which are apparently free but in reality are forced. More specifically, the current discussion tends to be orientated towards a concept of forced labour which includes these three distinctive elements:

- from a legal point of view, it is impossible for the worker to dissolve the relationship with his employer

- from the social point of view, the possibilities of significantly influencing employment conditions are limited

- there is a high mortality rate, which indicates a higher than average workload and a provision of means of sustenance below the necessary requirements.

See: [https://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/geschichte/auslaendisch/begriffe/index.html]

The workers' re-education camps (AEL) were set up in 1940 by the Gestapo in order to re-educate individuals accused of acts of industrial sabotage or who, for some reason, were held to be “reluctant” to work. In effect, these camps were also a means of exploiting forced labour. It has been estimated that in Germany and the German-occupied territories around 200 Arbeitserziehungslager had been set up in which around 500,000 people had been imprisoned.

During the Second World War the Germans established prisoner of war units known as Bau-und Arbeits Battaillon (shortened to B.A.B.). The B.A.B. were made up on average of 600 prisoners of war who were used as forced labour. The distinguishing feature of these forced labour units was that they were mobile; unlike the prisoners who were being held in the Stalag, these workers were not stationed in a specific location but were moved around according to necessity.

The I.G. Farben Company was founded in 1925 from the merger of several different German industries. During the Second World War it was the main producer of chemicals for Nazi Germany. I.G. Farben made more use of forced labour than any other industry, particularly during the construction of the plants at Auschwitz. The directors of I.G. Farben were among the accused at the Nuremberg Trials of 1947/48. At the end of the war the decision was taken to split up the industry into its original component parts.

The Arbeitskommando were work camps detachments for prisoners who had been captured by the Germans. Usually made up of a few hundred prisoners, they were set up near to places of employment (factories, mines, agricultural establishments etc.). They were run from a central Stalag (prisoner of war camp), which may have been responsible for hundreds of work detachments. The work detachments for Allied prisoners of war were visited on a regular basis by representatives of the Red Cross.

The Military Work Inspectorate was set up in October 1943 with the aim of organising a workforce which was to construct territorial defences for the Italian Republic of Salò and repair the damage caused by air raids. Known as the “Organizzazione Paladino” (Paladino Organisation) after its founder and commanding officer, and operating in strict collaboration with, and at times directly employed by, the Germans, it took on several tens of thousands of workers.

The Todt Organisation was begun in Germany at the end of the 'Thirties with the aim of setting up a workforce which would build military defences. The idea of Fritz Todd, who was also its director until his death in 1942, during the war it exploited forced labour in German-occupied countries. In Italy it played a fundamental role in the construction of defences along the Appenines in support of the Wehrmacht, employing tens of thousands of men.

Born in Scilla (Reggio Calabria) in 1890, he volunteered for the Corps of Engineers as a telegraphist in 1907. In 1908 he rose to the rank of sergeant, a rank he held throughout the War in Libya. In 1914 he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and during the First World War he was made captain.

Afterwards he remained in the Armed Forces and in 1932 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1936 he took part in the War in Ethiopia, during which he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the Second World War, he returned to Italy after participating in the Greek campaign and was assigned to the Bolzano Corps. In 1942 he was promoted to brigader general. After the armistice he joined the Italian Social Republic for which he created the Military Labour Inspectorate.

He finally retired in 1945 and in 1970 he was awarded the honorary grade of major general.

He died in 1974.

Fritz Sauckel, born in 1894, was a local Nazi party official. In 1942 he was nominated plenipotentiary for the organisation of work throughout all the German-occupied territories. In practice, he was responsible for the compulsory engagement of forced labour. In Italy his organisation tried to round up hundreds of thousands of men to send to the German Reich, with scarce results. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to death, the sentence being carried out in 1946.

Albert Speer, born in 1905, was an architect who enjoyed an excellent personal relationship with Adolf Hitler. Even though he was not an ardent Nazi, he was the brains behind the staging of the Party parades, thereby assuring for himself the esteem and trust of the dictator. In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt, he was put in charge of the Ministry of Arms and Munitions, which oversaw the Todt organisation. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to twenty years imprisonment. He died in London in 1981.

Fritz Todt was a German engineer who was responsible, in the 'Thirties, for building the motorway system as desired by Hitler. At the end of the 'Thirties he set up the Todt Organisation, with the aim of supplying forced labour to be used in the building of defences along the French border. During the war his organisation oversaw the use of forced labour in the occupied territories. He died in a plane crash in 1942.

The workers' re-education camps (AEL) were set up in 1940 by the Gestapo in order to re-educate individuals accused of acts of industrial sabotage or who, for some reason, were held to be “reluctant” to work. In effect, these camps were also a means of exploiting forced labour. It has been estimated that in Germany and the German-occupied territories around 200 Arbeitserziehungslager had been set up in which around 500,000 people had been imprisoned.

During the Second World War the Germans established prisoner of war units known as Bau-und Arbeits Battaillon (shortened to B.A.B.). The B.A.B. were made up on average of 600 prisoners of war who were used as forced labour. The distinguishing feature of these forced labour units was that they were mobile; unlike the prisoners who were being held in the Stalag, these workers were not stationed in a specific location but were moved around according to necessity.

The I.G. Farben Company was founded in 1925 from the merger of several different German industries. During the Second World War it was the main producer of chemicals for Nazi Germany. I.G. Farben made more use of forced labour than any other industry, particularly during the construction of the plants at Auschwitz. The directors of I.G. Farben were among the accused at the Nuremberg Trials of 1947/48. At the end of the war the decision was taken to split up the industry into its original component parts.

The Arbeitskommando were work camps detachments for prisoners who had been captured by the Germans. Usually made up of a few hundred prisoners, they were set up near to places of employment (factories, mines, agricultural establishments etc.). They were run from a central Stalag (prisoner of war camp), which may have been responsible for hundreds of work detachments. The work detachments for Allied prisoners of war were visited on a regular basis by representatives of the Red Cross.

The Military Work Inspectorate was set up in October 1943 with the aim of organising a workforce which was to construct territorial defences for the Italian Republic of Salò and repair the damage caused by air raids. Known as the “Organizzazione Paladino” (Paladino Organisation) after its founder and commanding officer, and operating in strict collaboration with, and at times directly employed by, the Germans, it took on several tens of thousands of workers.

The Todt Organisation was begun in Germany at the end of the 'Thirties with the aim of setting up a workforce which would build military defences. The idea of Fritz Todd, who was also its director until his death in 1942, during the war it exploited forced labour in German-occupied countries. In Italy it played a fundamental role in the construction of defences along the Appenines in support of the Wehrmacht, employing tens of thousands of men.

Born in Scilla (Reggio Calabria) in 1890, he volunteered for the Corps of Engineers as a telegraphist in 1907. In 1908 he rose to the rank of sergeant, a rank he held throughout the War in Libya. In 1914 he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and during the First World War he was made captain.

Afterwards he remained in the Armed Forces and in 1932 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1936 he took part in the War in Ethiopia, during which he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the Second World War, he returned to Italy after participating in the Greek campaign and was assigned to the Bolzano Corps. In 1942 he was promoted to brigader general. After the armistice he joined the Italian Social Republic for which he created the Military Labour Inspectorate.

He finally retired in 1945 and in 1970 he was awarded the honorary grade of major general.

He died in 1974.

Fritz Sauckel, born in 1894, was a local Nazi party official. In 1942 he was nominated plenipotentiary for the organisation of work throughout all the German-occupied territories. In practice, he was responsible for the compulsory engagement of forced labour. In Italy his organisation tried to round up hundreds of thousands of men to send to the German Reich, with scarce results. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to death, the sentence being carried out in 1946.

Albert Speer, born in 1905, was an architect who enjoyed an excellent personal relationship with Adolf Hitler. Even though he was not an ardent Nazi, he was the brains behind the staging of the Party parades, thereby assuring for himself the esteem and trust of the dictator. In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt, he was put in charge of the Ministry of Arms and Munitions, which oversaw the Todt organisation. He was tried at Nuremberg and condemned to twenty years imprisonment. He died in London in 1981.

Fritz Todt was a German engineer who was responsible, in the 'Thirties, for building the motorway system as desired by Hitler. At the end of the 'Thirties he set up the Todt Organisation, with the aim of supplying forced labour to be used in the building of defences along the French border. During the war his organisation oversaw the use of forced labour in the occupied territories. He died in a plane crash in 1942.